Youth who receive special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) and especially young adults of transition age, should be involved in planning for life after high school as early as possible and no later than age 16. Transition services should stem from the individual youth’s needs and strengths, ensuring that planning takes into account his or her interests, preferences, and desires for the future.

Listening Session Summary: Preparation and Process

AIR conducted careful and intentional preparation for more than six months. This included identifying participants (19 youth and 16 chaperones), planning travel/logistics for the participants, providing detailed guidance on strategic sharing to both youth and their chaperones, developing session materials, providing an onsite counselor, coordinating video vignettes, and co-facilitating all sessions at the meeting. Strategic sharing is a process of carefully deciding what to share about one’s personal experience (see page 5 for detailed explanation).

Participants

“We are not a statistic!”

Recognizing the importance of gaining the perspective of a variety of youth with varying experience, AIR worked with NRCCFI to recruit a diverse group of youth from across the country to learn about the youth’s needs, communication, visitation, services, and supports (see Appendix B for the list of youth-serving organizations that sent youth to participate). Of particular interest was learning how the youth maintain or build relationships with their parent(s) while the parent is incarcerated and how this affects the young person. Please note: the information gathered during this listening session cannot be considered representative of all youth with incarcerated parents.

Participants in the listening session were youth ages 15-23 with at least one parent who is or has been incarcerated. AIR received consent from each participant’s parent or guardian if the youth was under 18-years-old. The consent form stated that their participation was voluntary and confidential. They positively consented to three separate items: general participation in the meeting, audio taping of the sessions, and photo/video taping of their image during sessions for possible use in products posted on the youth.gov/coip website. Two youth did not consent to photo/videotaping. Four young women consented to provide short “video vignettes” (see Figure 1) sharing their experiences with having a parent behind bars (see Appendix C for a list of the questions used for these vignettes).

FIGURE 1: VIDEO VIGNETTES — IN THEIR WORDS: 4 YOUNG PEOPLE SHARE EXPERIENCES WITH HAVING AN INCARCERATED PARENT

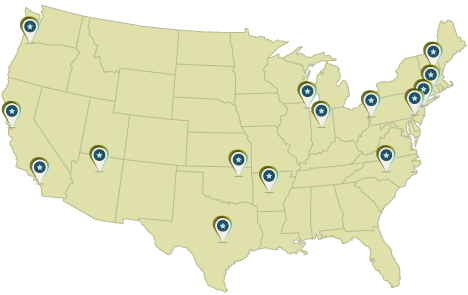

Listening session participants included 19 youth from organizations in 13 states (see Figure 2). The 13 females and six males had a variety of backgrounds and experiences, including race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, whether they were English-language learners and/or first generation in the United States, geography and sovereign nation status (i.e., regional, urban, suburban, rural, tribal), whether it was their mother and/or father incarcerated, the length of parental incarceration, their age — now and at time of incarceration, whether they lived with or apart from their parent prior to incarceration, their living arrangements during incarceration, their relationship with parents and family, any history of personal or sibling juvenile/criminal justice involvement, communication and visiting schedule with incarcerated parent(s), and distance from where they lived to prison (see Appendix A for an infographic about participant background and demographic data, which is based on responses to a survey administered prior to the listening session).

FIGURE 2: PARTICIPANT LOCATIONS

Source: Locations of organizations that sent youth to listening session (see Appendix B)

Strategic Sharing

Prior to the listening session, AIR and NRCCFI worked with the youth and their trusted adult to prepare them for their visit to Washington, D.C. A trusted adult could be a parent or family member, a mentor, or a staff person from a youth serving organization. Preparation included holding several conference calls to discuss logistics, answer questions, and describe the strategic sharing process. We explained to them how to think through carefully with a trusted adult what they wanted to share publicly about their personal experience and why. We let the youth know that they did not need to answer any questions with which they were not comfortable. To assist with prioritizing the safety and privacy of the youth, we asked that the Federal partners who attended the listening session be careful about what they asked youth to share and consider why they were asking each question. We reminded all adults at the session that youth often feel pressured to share their stories, even if doing so is costly to them, but that trusted adults should always prioritize the safety of youth.

Prior to the listening session, AIR and NRCCFI worked with the youth and their trusted adult to prepare them for their visit to Washington, D.C. A trusted adult could be a parent or family member, a mentor, or a staff person from a youth serving organization. Preparation included holding several conference calls to discuss logistics, answer questions, and describe the strategic sharing process. We explained to them how to think through carefully with a trusted adult what they wanted to share publicly about their personal experience and why. We let the youth know that they did not need to answer any questions with which they were not comfortable. To assist with prioritizing the safety and privacy of the youth, we asked that the Federal partners who attended the listening session be careful about what they asked youth to share and consider why they were asking each question. We reminded all adults at the session that youth often feel pressured to share their stories, even if doing so is costly to them, but that trusted adults should always prioritize the safety of youth.

We had a trained counselor in attendance at the listening session who was available at any time for youth who needed to talk or process the experience. Several youth availed themselves of the counselor’s services. At the closing of the session, the counselor shared that participants should not be surprised if they experienced a delayed reaction to the public sharing experience and the stories and memories they revealed. She advised the chaperones and trusted adults to check in with the youth in the days immediately following the event.

Facilitation

Three senior AIR staff members and one NRCCFI staff member co-led the sessions, and two AIR staff took notes. Participants were not compensated for their time but had all expenses paid for the trip. The facilitators reminded the participants that they were not required to answer all of the questions and that there were no right or wrong answers. The participants and facilitators sat in an informal circle and everyone had the opportunity to speak as much or as little as they chose.

Three senior AIR staff members and one NRCCFI staff member co-led the sessions, and two AIR staff took notes. Participants were not compensated for their time but had all expenses paid for the trip. The facilitators reminded the participants that they were not required to answer all of the questions and that there were no right or wrong answers. The participants and facilitators sat in an informal circle and everyone had the opportunity to speak as much or as little as they chose.

Participants shared their experiences, offering insights into the challenges they face and ideas for change for improved opportunities and outcomes. It was the impression of the facilitators that participants spoke openly as demonstrated by their willingness to volunteer their time and feedback knowing there was no reward (monetary or otherwise), and the emotion and passion with which they shared their stories without being prompted.

The two-day listening session consisted of a day of facilitated small group discussion, followed by a day of presentation to, and question and answer with, federal guests. AIR also held a separate break-out session on day one for the chaperones who accompanied the youth to D.C. Separate sessions maximized youth voice and allowed the youth to be comfortable speaking openly in their sessions, while also giving the chaperones an opportunity to share the valuable perspective of caregivers or trusted adults (see Appendix C for a full list of questions asked to each group during the listening session).

» Return to Listening Session Summary: Overview page.

» Return to Youth Perspectives page.

Research links early leadership with increased self-efficacy and suggests that leadership can help youth to develop decision making and interpersonal skills that support successes in the workforce and adulthood. In addition, young leaders tend to be more involved in their communities, and have lower dropout rates than their peers. Youth leaders also show considerable benefits for their communities, providing valuable insight into the needs and interests of young people

Statistics reflecting the number of youth suffering from mental health, substance abuse, and co-occurring disorders highlight the necessity for schools, families, support staff, and communities to work together to develop targeted, coordinated, and comprehensive transition plans for young people with a history of mental health needs and/or substance abuse.

Nearly 30,000 youth aged out of foster care in Fiscal Year 2009, which represents nine percent of the young people involved in the foster care system that year. This transition can be challenging for youth, especially youth who have grown up in the child welfare system.

Research has demonstrated that as many as one in five children/youth have a diagnosable mental health disorder. Read about how coordination between public service agencies can improve treatment for these youth.

Civic engagement has the potential to empower young adults, increase their self-determination, and give them the skills and self-confidence they need to enter the workforce. Read about one youth’s experience in AmeriCorps National Civilian Community Corps (NCCC).